Yoga teacher, Charlotte Watts explores the relationship between our digestive health and wellbeing in a blog series. In the second of the series, find out how yoga helps unravel modern postural issues that affect digestion

In part one of this series we looked at the effects of stress on the gut. This showed how our digestive system is bound up in our relationship with the world around us. It makes sense that our postural issues affect our digestion. As our physical being (annamaya kosha or physical layer in yoga) is how we meet and relate to the world, our postural habits affect our digestive function and, as we will also explore in the next episode, out into movement patterns themselves.

Postural issues and digestion

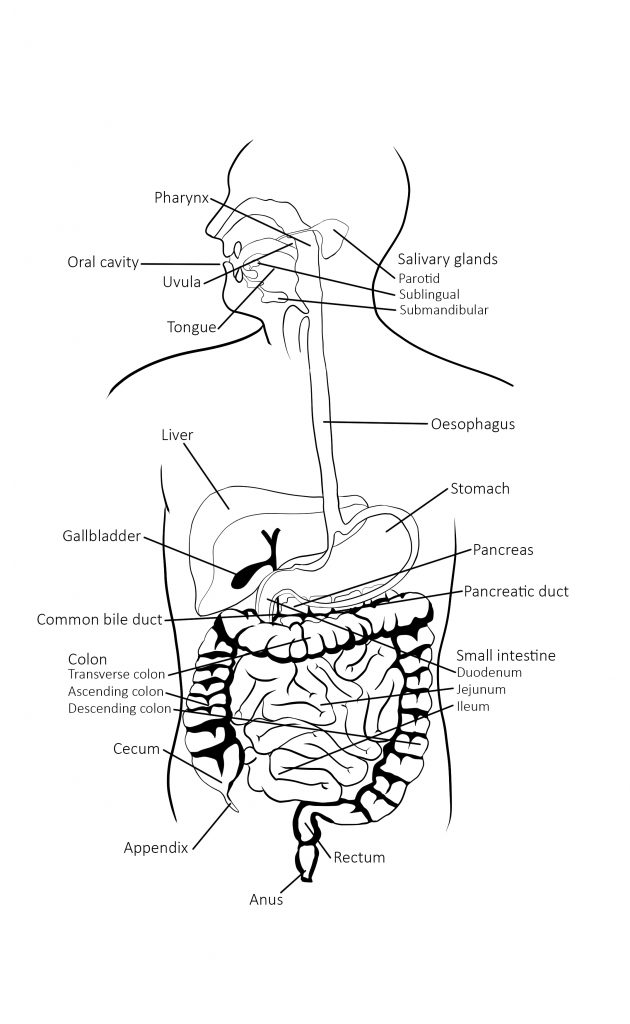

A key detail in our human digestive tract design is that our physical design is stacked up vertically from the ground. Our digestion has to follow this organisation. The human oesophagus (where the food goes down) and rectum (where the waste comes out!) are vertical to the ground, unlike other animals. Our digestive processes rely on these and many other related aspects of posture to optimally function.

The emotional psoas and the diaphragm

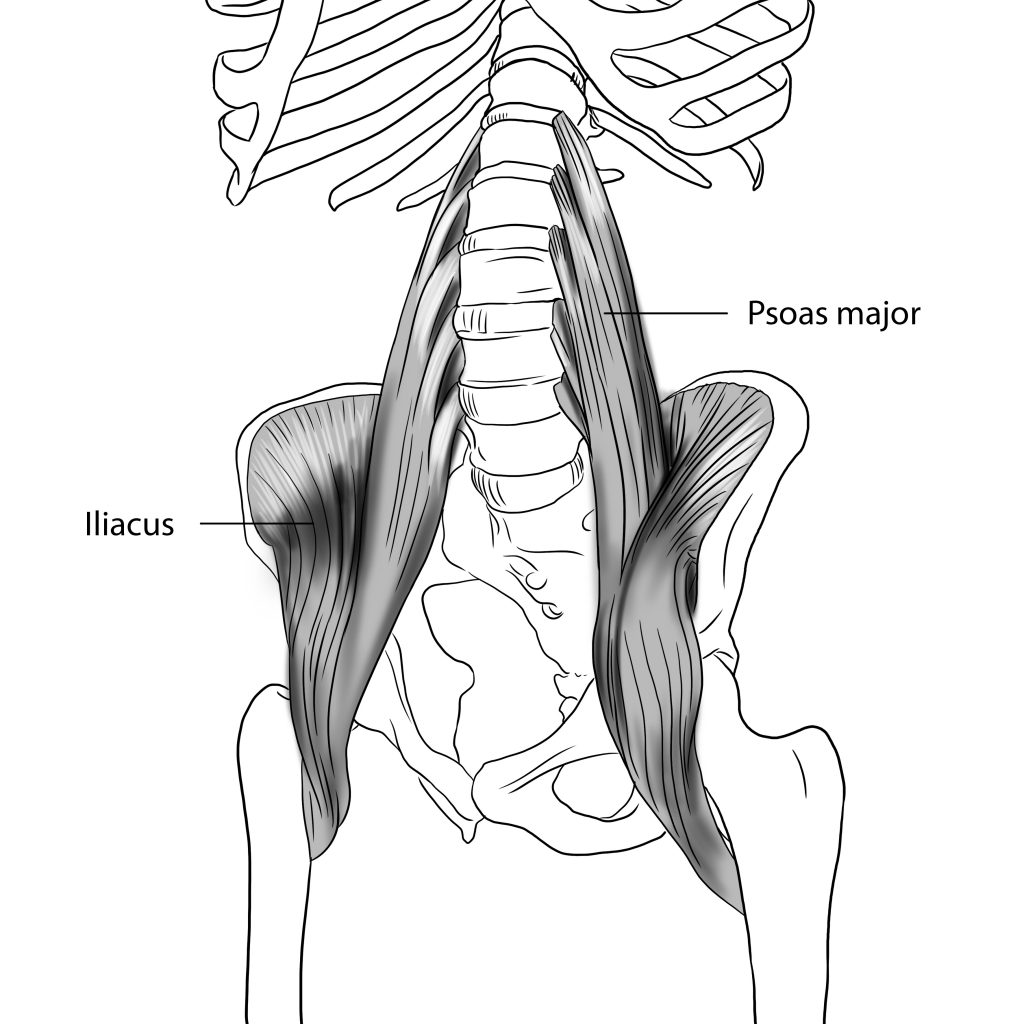

This brings us back to the emotional psoas muscle (discussed in part one). The psoas muscle can be greatly affected by chronic stress, especially alongside modern postural patterns. These are generally a result of sitting on chairs for long periods of time. This being essentially sedentary and hunching over for much of the time, means standing upright through the front body and abdomen can be difficult; creating tension in the back, shoulder and jaw muscles – that relays back down to the gut as stress.

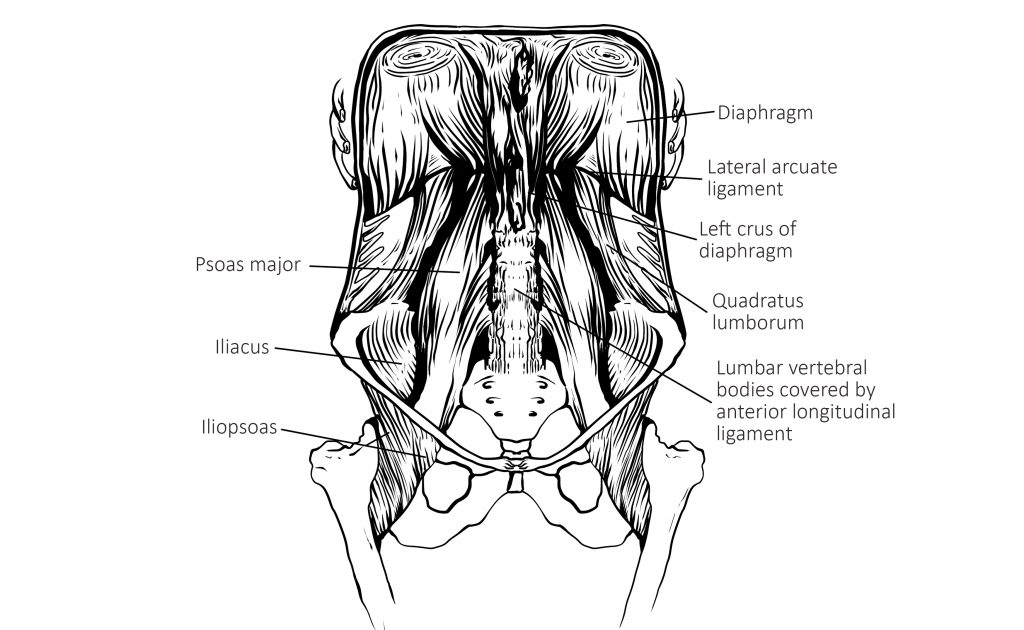

The psoas joins the diaphragm in such an intertwined way that we can view them as part of one continuum; always working together. Collapse in the chest from slumping, trauma and even shame affects how we breathe, limiting diaphragmatic movement that is crucial for digestive function; as a kind of regulatory internal self massage. Also, downward motion of the diaphragm helps us to expel faeces (poop) with ease, rather than straining through clenched teeth and pushing down into the pelvic floor.

Our stomach and our liver are nestled up into the diaphragm and attached there by fascia (connective tissue). If the diaphragm doesn’t move in a pulsing way as we breathe in and out, those tissues can get stuck and tight. This can mean less efficient breakdown of food in the stomach, but also pushing forward the oesophagus forward, a contributing factor to acid reflux and even hiatus herniation, where a portion of the stomach pushes through the diaphragm.

Fascial slide-and-glide for gut motility

All fascial connections need free movement – often referred to as ‘slide and glide’. Within the digestive tract this means that organs can pump, pulse and move (mobility) and that the gut wall has good internal movement (motility) as peristalsis, which keeps stuff moving through in a downward direction from the mouth to the anus.

Without good gut motility, food ends up hanging around partially digested, creating gas, putrefaction and stagnant waste. This can contribute to symptoms such as those seen in IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome), not least from Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth or SIBO, where beneficial bacteria that should live in the large intestine, flood into the small intestine and don’t get washed back down.

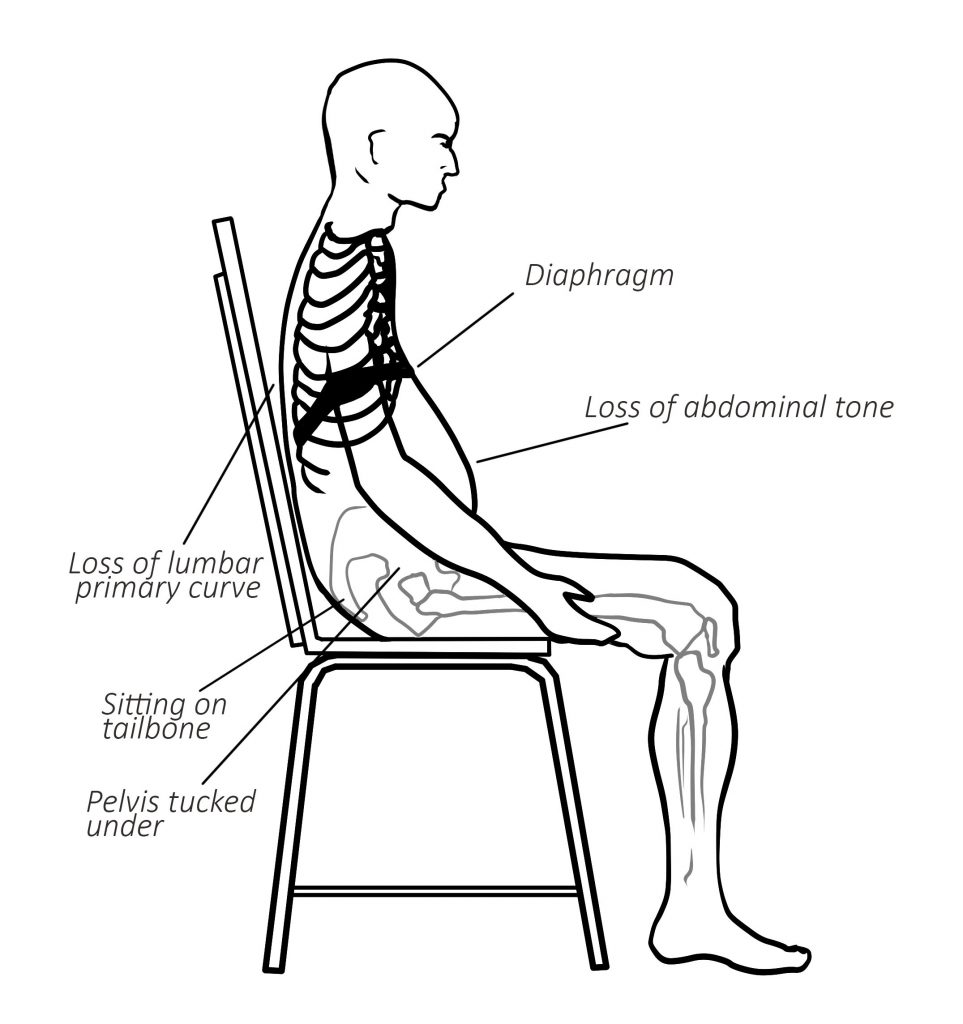

Chair Slumping

We can see how our diaphragm can struggle to have the space and the freedom it needs when we look at a very common way of sitting onto chairs. Sitting back on to the tailbone rather than to the front of the sitting bones constricts our natural primary curve at the lower back. The diaphragm is inhibited by collapse in the chest. When we don’t need to lift up through the front body to sit upright, there is loss of natural abdominal tone, where the digestive organs are contained for best function.

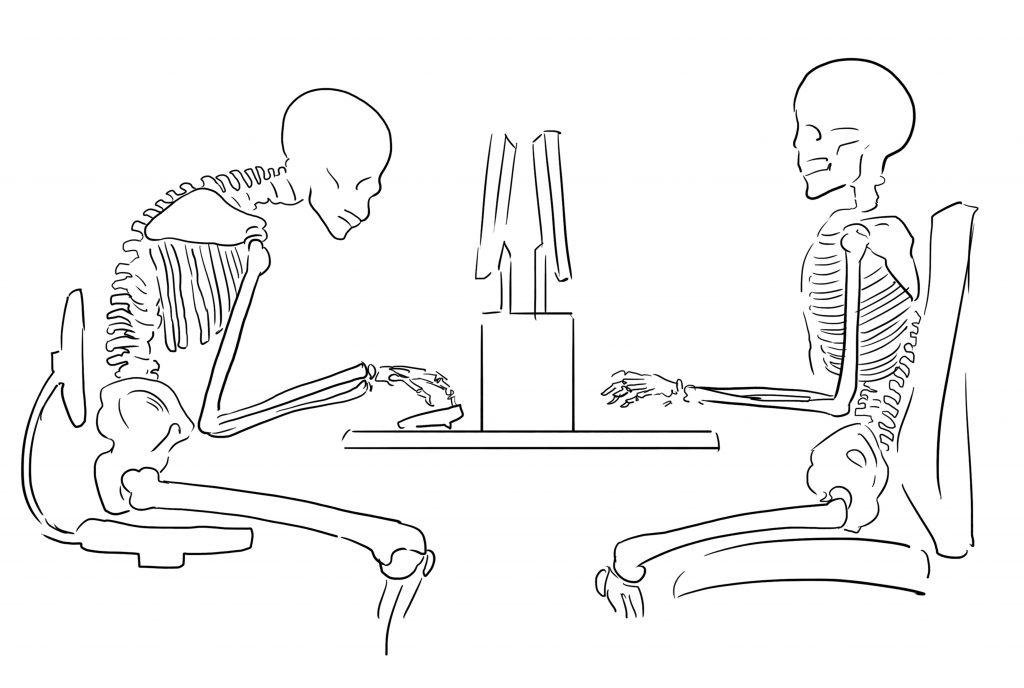

Slumping over a desk is a common working position. Many computer users stay in this position for as many as 8-10 hours a day. Look at the skeleton on the left hand side in the picture below. We see a posture where the head pushes forward of the shoulders. The ribs point downwards, where there’s little room for the organs. Tissues can quickly lock into these positions as their norm. Many people also eat in this position. The passage of food through the throat and into the stomach is a difficult journey. If we add in mindless eating, less conscious chewing means food reaches the stomach in a much thicker consistency than ideal. This style of eating is often present with the stress response. The eater is doing, thinking, worrying, focusing, which proves further impingement of the digestive processes.

Diaphragmatic breathing in Constructive Rest Position

Opening up the body in a kind and progressive way is what the psoas and diaphragm need. This starts to unravel held patterns that affect both breathing and digestion; also keeping up continual stress states as they prevent accessing relaxation responses.

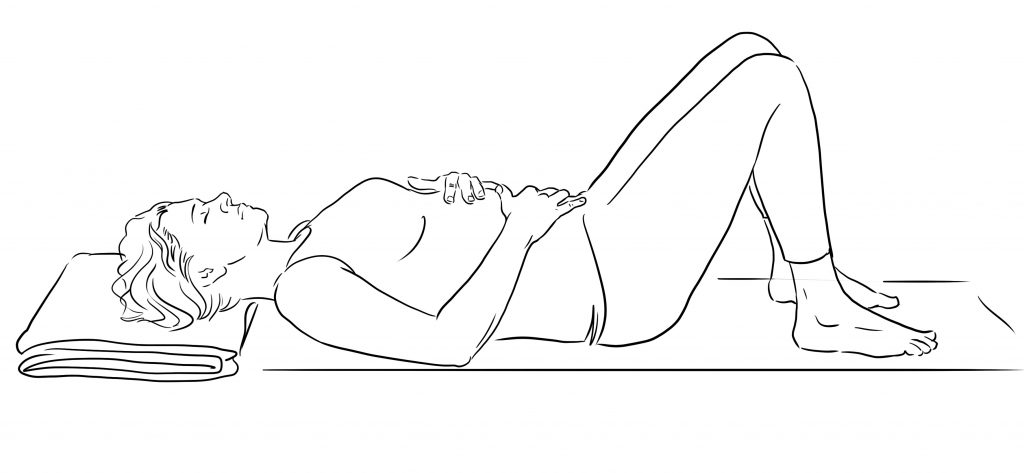

Constructive Rest Position (CRP) shown below is one of the best to be able to stay and notice both the breath and the diaphragm. This also gives the psoas the chance to unravel and release that it needs. The psoas is one of the few muscles in the body that always needs releasing rather than strengthening. Supporting our posture in this way has a far reaching effect on our ability to digest both our food and our life experiences.

Lying down in CRP as shown with one hand on belly, one hand on the diaphragm can help us tune in to the movements of the diaphragm. The chest and the solar plexus area can feel free, open and spacious. Here we can invite the belly to move alongside the motion of the breath. The belly rises as the chest expands in the inhalation. It drops with the downward motion of the diaphragm as the lungs empty.

Addressing postural issues and digestion

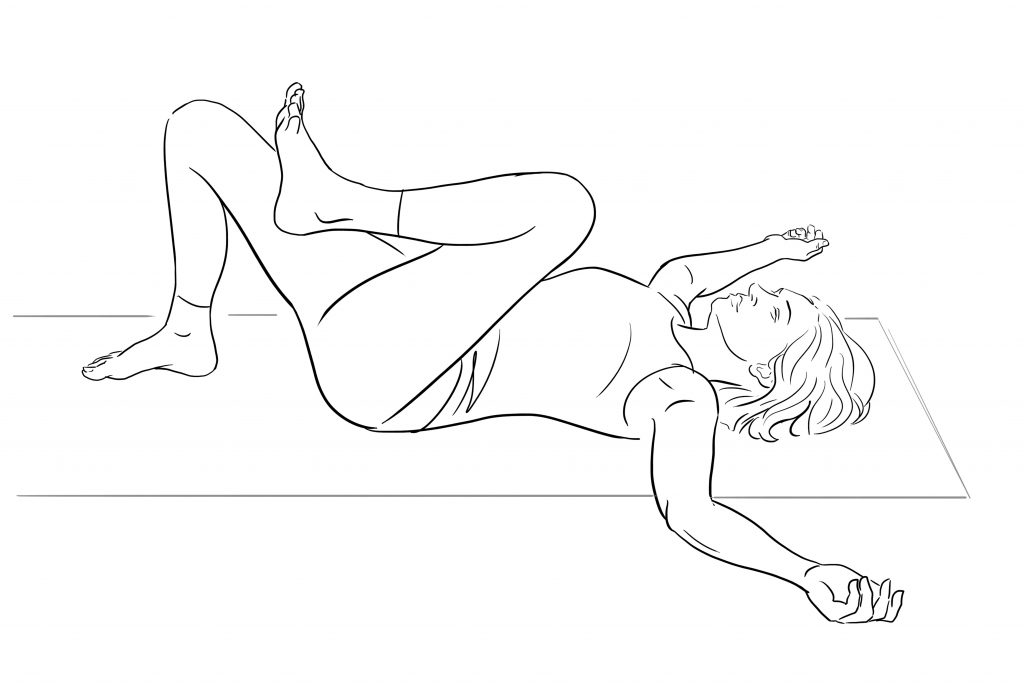

Lying down is a great start to a practice as it allows us the space to observe our internal landscape without the effort of raising ourselves up vertically from the ground. We tend to hold tension in the upper back, shoulders and jaw. We see this in the vicious cycle of stress, sedentary posture and restricted motion in the diaphragm. By Exploring what our bodies need from here, we can then start to create the fascial slide-and-glide. This is what we need for ease of mobility and motility in the gut.

About Charlotte Watts:

Charlotte Watts is a Senior Yoga Teacher with a love of explorative, compassionate and somatic yoga practices. Her influences include Qi Gong and Feldenkrais. Charlotte is the author of Yoga Therapy for Digestive Health (Singing Dragon 2018). She is also an award-winning nutritionist. Charlotte has practiced since 2000 and specialises in stress-related and fatigue conditions and burnout, and digestive issues. Charlotte teaches modules for Teaching Yoga for Stress and Burnout; for CFS/ME and for Digestive Health for Yogacampus and on the Yoga Therapy course for The Minded Institute

Leave a Reply